This article first appeared in Australian Yoga LIFE Magazine issue 38 in March 2013, and is reproduced here by kind permission of AYL.

The shoulder is an amazing joint. Having developed to allow our ancestors to swing through the trees, a fully functional shoulder joint allows 360 degrees of rotational movement as well as being able to support the weight of the entire body. However, this combination of the largest possible ROM (range of movement) of any joint plus adequate strength is a delicate one, and shoulders can get into trouble when the balance is upset.

In the current ‘computer age’, many people have jobs which require sitting for long periods at a desk. This hunched forward position tends to lead to rounded shoulders and upper back, and a closed chest. Over time the muscles of the chest, shoulders and back become tightened and this position becomes the default. As is the case with every joint in the body, the bio-mechanics of the shoulder joint do not exist in isolation. The full ROM of the shoulder joint is dependent not only on flexibility of the shoulder muscles themselves, but also on having a mobile thoracic spine and an open chest. Therefore a rounded shouldered/closed chest posture is often the cause of compromised action of the shoulder joints. Soreness and tightness the shoulders and up into the neck is one result, with another being a predisposition to common shoulder injuries unless care is

The good news is that yoga practice has the ability to both reverse that rounded shouldered and closed chest posture, as well as increase the flexibility of the shoulder muscles directly. Together these two approaches can facilitate full range of movement of the shoulder joint over time.

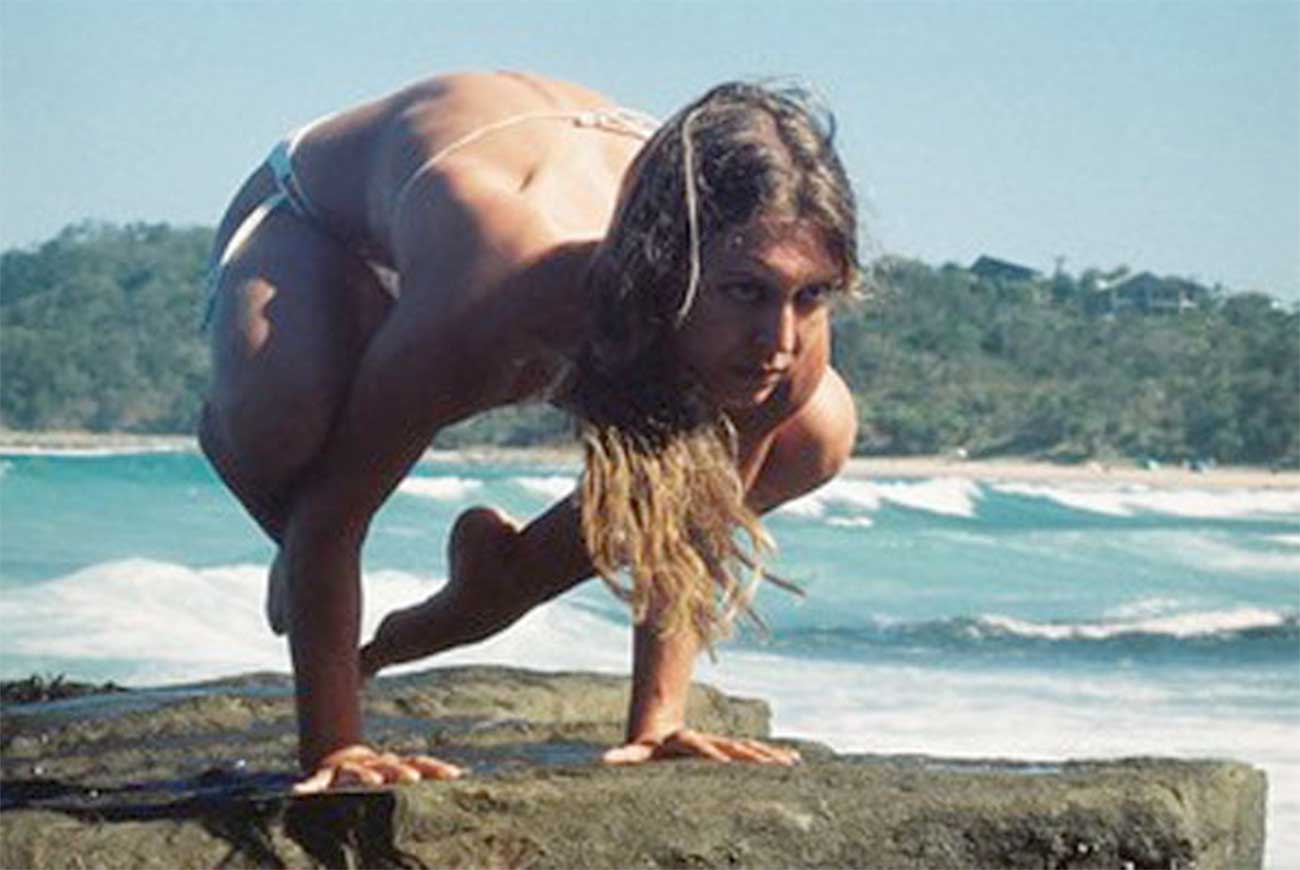

Shoulder mobility also relates to shoulder strength, and weight bearing. To safely ask the shoulders to perform strong weight bearing techniques, we need to have FIRST attained a pre-requisite level of all round shoulder mobility. (This depends not only on the flexibility of the shoulder joint itself, remember, but also on the overall posture?an open chest and mobile thoracic spine being the ideal.)

If the shoulders are rounded and tight, they are not in a good position bio-mechanically to then do a lot of weight bearing, and strain in certain muscles and tendons can often be the result.

In this, and the following article on the shoulder, we shall look at the bio-mechanics of the shoulder and what we can do to improve the functionality of the joint through yoga. In this first part we shall focus on improving shoulder mobility, by working on reversing a rounded shouldered posture, and improving flexibility of the muscles themselves. In the next article, we shall focus on strength and stability-and the difference between the two.

First let us look at the peculiarities of the shoulder joint that make it prone to strain, and some common injuries that do occur.

Anatomy of the Shoulder

The shoulder joint has the largest possible ROM of all the joints; almost 360 degrees of movement is possible if the joint is fully functional. This large ROM is made possible by its structure. It is a ball and socket joint that has a large ball and a very shallow socket, allowing for a lot of movement-but comparatively minimal stability. Unlike the hip joint (which is also a ball and socket joint, and has much a much deeper socket and stronger/thicker ligaments,) the ligaments of the shoulder joint are small and thin to allow for its great flexibility. The strength and stability of the shoulder joint are not provided by the shape of the articulating bones or its ligaments; instead, the rotator cuff muscles and their tendons surround and enclose the joint in a circular fashion. The muscles themselves therefore need to serve as stabilisers to the joint as well as providing the movement. In short, the muscles and ligaments of the shoulder need maximum flexibility to allow for a wide range of motion but also need to be strong enough to allow for actions such as lifting, pushing, pulling, and weight bearing. If this delicate balance of flexibility and strength is upset, the shoulder joint can get into trouble, especially during strong weight bearing postures.

Muscles of the Shoulder Joint

Rotator Cuff

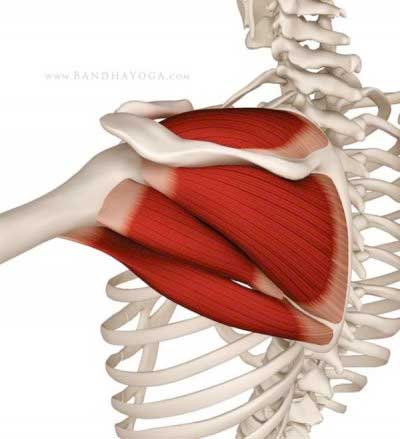

The rotator cuff are four muscles that surround the joint, serving to hold the bones in place and give the joint most of its stability, as well as providing 90% of its movements. All of these muscles originate on different parts of the scapula (shoulder blade) and cross the shoulder joint to insert upon the humerus (upper arm bone). Each of them needs full strength and flexibility in order for the shoulder joint to function optimally. They are:

Supraspinatus

Rotator Cuff Muscles from top down; Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, Teres Minor, Teres Major.

This muscle abducts the arm (moves it away from the body).

Tightness in this muscle limits movements in postures that require the arm to move across the chest, such as the Garudasana (Eagle Pose) arm position.

Weakness or injury limits the ability to lift the arms out and away from the body, resulting in ‘shrugged shoulder’ appearance in the arm position of Virabhadrasana II (Warrior Pose).

Weakness or injury will mean that other muscles (the upper trapezius and deltoids) will try to ‘help’ in postures such as Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward Facing Dog pose) resulting in shoulders ?hunched? around ears.

Infraspinatus

This muscle externally rotates (turns out) the arm.

Tightness limits the reverse prayer behind the back arm position in Parsvottanasana, (Side Stretch Pose) and the lower arm in Gomukhasana (Eagle Pose).

Weakness limits external rotation in postures such as Urdvha Dhanurasana (Upward Bow Pose).

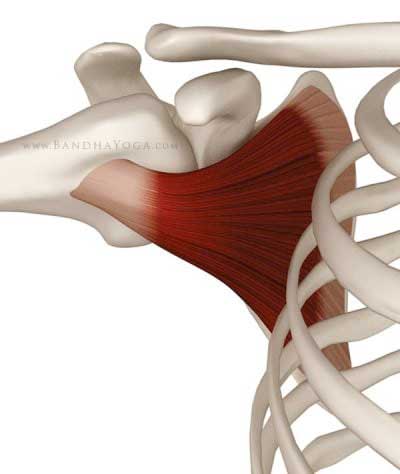

Subscapularis

This muscle internally rotates the arm (turns it inwards).

Tightness limits external rotation of the arm such as in Urdvha Dhanurasana (Upward Bow Pose) and Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward Facing Dog pose) and the upper arm in Gomukhasana (Eagle Pose).

Weakness limits the reverse prayer behind the back arm position in Parsvottanasana, (Side Stretch Pose) and the lower arm in Gomukhasana (Eagle Pose).

Teres Minor

This muscle is a synergist (‘helper’) of Infraspinatus; it externally rotates, (rolls out) extends (moves from raised to lowered position) and adducts (brings in to body) the arm.

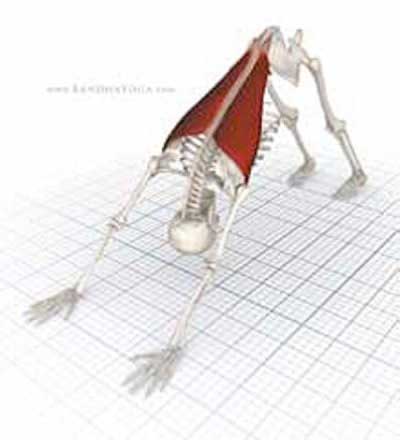

Diagram 3 – Latissimus Dorsi in Down Dog

Latissimus Dorsi

Another muscle that, when tight will limit the external rotation of the arm in Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward Facing Dog pose) is Latissimus Dorsi. This large back muscle has to stretch in Downward Dog to allow the back to lengthen-and as it inserts on the inside edge of the upper arm bone, and when contracted acts to rotate the arms inwards, it also has to stretch to allow the upper arms to rotate outwards. Working with Tadasana arms raised and Downward Dog as suggested below (see pics 6 & 7) will help to stretch Latissimus Dorsi.

Rotator Cuff Injury

This is the most common shoulder injury of them all, due to the structure of the shoulder joint itself. Two of the cuff muscles (infraspinatus and supraspinatus) actually pass underneath the acromion of the scapula bone, meaning that wear easily occurs. Chronic wear and tear frays the tendons, weakening them and subsequently producing an inflammatory response.

What often creates this wear and tear is repeatedly placing the arms in a raised position (think Downward Facing Dog pose) as this is the position in which the cuff muscles are pressed beneath the acromion. Supraspinatus is the muscle that is the most commonly injured in this way, becoming partially torn or irritated. It is aggravated by continual raising of the arms without adequate ability to externally rotate the arms/shoulders.

Working with the Shoulder in Yoga Postures

If we have a round shouldered/closed chest posture, and weakness/tightness in the shoulder and back muscles themselves, what tends to happen is that when we raise the arms above the head, we end up with the shoulders hunched around the ears, and the arms rolling inwards in their sockets. This position is one that can potentially lead to irritation of the supraspinatus.

One posture in which this would manifest would be raising the arms above the head in Tadasana (see pic.1) In this case, the trapezius muscles are ‘helping’ to lift the shoulders and we get that hunched shoulder appearance.

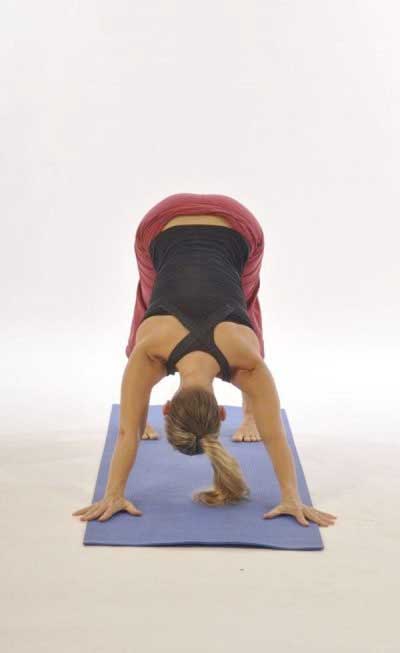

When we translate this same dynamic to Downward Facing Dog pose, in which there is also weight being born on the upper limb, we greatly increase the risk of wearing and injuring supraspinatus. (See Pic. 2)

Pic 1: Tadasana arms raised with hunched shoulders and arms internally rotated-incorrect (compare with pic 6)

Pic 2: Downward Facing Dog pose with hunched shoulders and arms internally rotated-incorrect (compare with pic 7)

Minimising shoulder strain in Yoga Practice

- In yoga settings nearly all shoulder injuries are repetitive strain injuries. If the shoulder is already injured and inflamed, the first stage is to REST. That means no weight bearing postures on the upper limb until the inflammation has subsided.

- If there is a round shouldered and closed chest posture, we can work gently and gradually to reverse this tendency over time.

The following practices are ideas on how this may be approached. However remember that all students are unique and have their own individual peculiarities, and these would ideally be taken into account in a one-on-one setting with a qualified yoga teacher or therapist.

Tadasana – Back to wall

Stand close enough to the wall so that the buttocks are touching the wall. Close the eyes and notice the breath. Start to slow down and smooth out the breath a little at a time. Cultivate an easy abdominal breath. Start to move the backs of the shoulder blades into the wall. Gradually see if you can allow the elbows to touch the wall. Then get the little fingers to touch the wall. See if you can feel the back of the head touching the wall or try to move it closer to the wall. (Make sure that you are not tipping the head back and allowing the chin to lift-keep the neck in line with the rest of the spine). Breathe in to the space between the shoulder blades; try to expand that space so that it touches the wall. On the out breath gently draw the abdomen inwards and upwards.

Stay in the pose for 5 minutes if comfortable.

Practice 3-6 times per week.

Upper back over a rolled blanket

Roll part of a blanket or towel up tightly so that it won’t flatten. Make sure the roll is not too thick; it should only be about 10-12cm in diameter max. Place the roll across the mat and with bent knees lie back over it. The roll should have its apex at about ‘bra-line’; just beneath the shoulder blades. The back of the shoulders should be comfortably on the floor and the neck should not arch back. (If not, the roll is too thick.) A folded blanket can be used behind the head to lengthen the neck.

Take the arms out at the sides to where is comfortable. Close the eyes and focus on the breath. Cultivate an easy abdominal breath.

Stay in the pose for 5 minutes if comfortable.

Practice 3-6 times per week.

Improve external rotation of the shoulder

In a yoga setting, one of the most basic and important movements of the shoulder is external rotation, or ?rolling the shoulders out? as you may have heard your teacher asking you to do in poses such as Downward Facing Dog. Once the chest is relatively open, we are in a good position bio-mechanically to improve this action.

Improving external rotation of the arms will also help decrease irritation if supraspinatus is irritated. A test is to roll arms inwards?if that is sore, you have an irritated supraspinatus. If there is soreness rolling the arms out, you have irritated infraspinatus?.which is less common in a yoga setting.

The following practices are examples of how we may approach improving the external rotation of the shoulder in some students.

Supine arm raises with block

Lie on the back with the knees bent. Place a foam yoga block long ways between the palms, arms close to the front body.

As you inhale lift the arms up as high as is comfortable without the elbows bending or the palms coming away from the block. Exhale as you lower the arms back down.

Practice 10 rounds 3-6 times per week if comfortable.

Tadasana arms raised with dropped shoulders and external arm rotation

Stand in Tadasana. Activate the fingers, with palms turned in towards the sides. Inhale as you raise the arms as high as you comfortably can-without the shoulders hunching, or the elbows bending. Keep the palms facing each other. Keep the chest open. Exhale as you take the arms back down.

Practice 10 rounds 3-6 times per week if comfortable.

Improve external rotation of the shoulder

In a yoga setting, one of the most basic and important movements of the shoulder is external rotation, or ?rolling the shoulders out? as you may have heard your teacher asking you to do in poses such as Downward Facing Dog. Once the chest is relatively open, we are in a good position bio-mechanically to improve this action.

Improving external rotation of the arms will also help decrease irritation if supraspinatus is irritated. A test is to roll arms inwards?if that is sore, you have an irritated supraspinatus. If there is soreness rolling the arms out, you have irritated infraspinatus?.which is less common in a yoga setting.

The following practices are examples of how we may approach improving the external rotation of the shoulder in some students.

Downward Facing Dog pose with external arm rotation

Begin on the hands and knees. Take the hands wider than shoulder width apart-right to the edges of the mat. Turn the hands slightly outwards, so that the index fingers are pointing towards the outside edges of the mat a little. Lift the shoulders away from the ears. Round the upper back a little to spread the shoulder blades wide apart. Inhale and as you exhale lift the hips up and back. Drop the head. Maintain a feeling of broadness between the shoulder-blades even if that means allowing your weight to move forward into the hands a little. Maintain the feeling of rolling the upper arms outwards-as if you would like your arm-pits to see the sides of the ribs. Keep the shoulder tops lifting away from the ears. Don?t let the elbows bend. Keep the palms pressing into the mat, and slightly ‘twist’ the palms outwards into the mat.

Stay in the pose for 5-10 slow breaths if comfortable.

Rest in Child pose. Then repeat.