This article first appeared in Australian Yoga Life Magazine in 2015, and is reproduced here by kind permission of AYL.

Adho Mukha Svanasana, or Downward Facing Dog Pose is one of those postures that as regular yoga practitioners, we do a lot-maybe up to 10 times a day. Because of this, how we come into and maintain the pose is bound to have a deep effect on our physical body, and beyond. Because of the frequency that we use the pose, the familiarity of it, we need to be especially mindful that we don?t ?tune out? and come into the pose in a habitual way, without true inquiry into how it is affecting us, each and every time, each and every breath.

I often say to my students, that Downward Dog is a little like a whole practice in itself-highlighting our areas of physical tightness and weakness, and also showing our approach to our practice as a whole (whether one of softening, accepting and being where we are right now, or pushing past the point of comfort, ease and stability in the pose to achieve an imagined ‘goal’).

Coming into an ?ideal? Downward Dog presents challenges for nearly all students in one way or another-and thus can take a lifetime (or longer) to master.

As with any asana, there are many different instructions given, and many different ways to practice the pose. Each of these different ways will have different effects-we just need to be clear about the effects that we want.

The Ideal

Over the years, I have come to understand that to get the physical and pranic effects that I want (for myself and my students) out of the pose, it is necessary to prioritise minimising any distortion to the shape of the spine. In other words, to come into the pose in a way that maintains the natural lumbar lordosis, or hollow, and thoracic kyphosis, or broad upper back-just as in a natural standing position.

The physical benefits of this include keeping the neck relaxed, and the shoulders un-tensed, and in maintaining free movement of the diaphragm so that breathing can be full and easy. Having a full and easy breath is even more beneficial to the physiology as a whole if there is uncompromised movement of the spine around the breath, with none of the muscles around the spine, or the spinal discs being overly tensed or compressed.

As for the pranic benefits, maintaining the natural curves of the spine and a full and easy breath means that we are getting the effect of improving and balancing both prana and apana with each breathing cycle.

The inhalation, and the area from navel to throat (the thoracic area) relate to prana. On the inhalation, from it’s natural kyphosis, (broad and slightly rounded at the back) the thoracic spine slightly extends (flattens or hollows). The heart centre lifts and moves towards the chin (resulting in a subtle jalandhara bandha at the top of the inhalation.) The back of the chest also being broad and open is important here to expand the prana area all around in three dimensions around the spine and not just through the front chest. All of this leads to an increased level of and greater effect from prana, the energy involved with vitality and vigour, and courage.

The exhalation, and the area of the lower abdomen to the pelvic floor (the lumbar area) relate to apana. On the exhalation, from it?s natural lordosis (hollow at the back) the lumbar spine slightly flexes (moves towards flat). The navel moves in and upward towards the heart (resulting in a subtle uddiyana bandha and mula bandha at the end of the exhalation). All of this leads to an increased effect of apana, the energy involved with elimination, release, and surrender.

(Downward Dog is in fact a whole body mudra and is often used in classical hatha yoga as a way to teach the bandhas).

How?

How do we move towards this ideal intelligently? What limits us in achieving this goal?

Thoracic Spine, Shoulders and Neck

To achieve the relaxed neck, relaxed shoulders and broad upper back, and minimal distortion to the natural shape of the thoracic spine requires very good shoulder rotation. Without it, those with tight shoulders will find that the elbows want to bend, the hands want to turn in, and the shoulder blades squeeze in towards the spine, jamming the thoracic spine restricting movement and ease in the whole upper body.

Quick Fix

To compensate for tight shoulders and lack of shoulder rotation whilst in the pose, take the hands wider apart. This gives more space at the shoulder joint to compensate for the tightness, and minimises distortion and tightening in the neck and upper spine.

Hands can also be turned out (index finger, rather than middle fingers parallel, or even slightly turned outwards). This again compensates for the lack of rotation at the shoulder joint itself.

Long-Term Fix

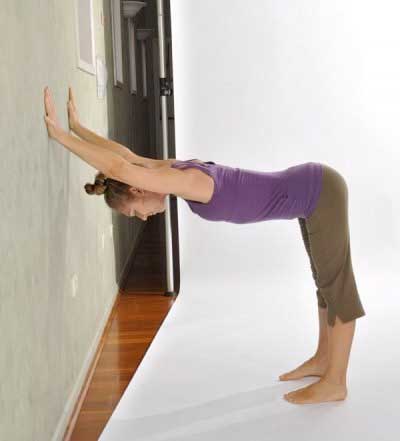

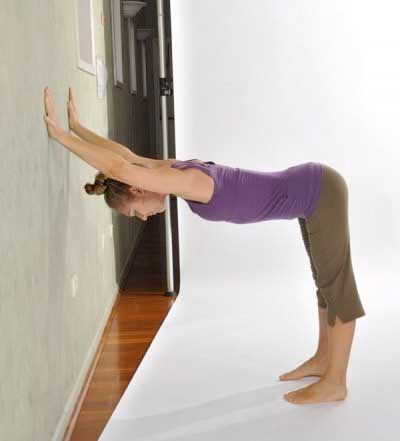

Reduce tightness and improve shoulder mobility in simple non weight bearing postures, (such as raising the arms in Tadasana without bending the elbows and keeping palms parallel) and progress to stronger stretches to improve external rotation such as Half Dog with the hands to the wall.

Lumbar Spine

Maintaining the natural shape of the lumbar spine in the pose requires everything that is needed to achieve any good forward bend-good hip flexion (ability to tilt the pelvis forward) which in turn requires flexible hip rotator muscles and hamstrings, and a strong but flexible lower back.

Tight hips and hamstrings, tight lower back – The forward bend complex

Downward Dog Incorrect:

Those with tight hips and hamstrings will compensate by rounding the lower and mid back. Pushing more with the hands to try to move the belly closer to the thighs then moves the spine further out of alignment by flattening or hollowing the upper back.

If instead the hips, hamstring and lower back are tight (or, in the case of the lower back, weak) rather than the whole pelvis tilting forward in the pose so that the tail bone points at the ceiling, and there is an acute angle between the lower belly and the upper front thighs, instead the lumbar will round to compensate.

This complex is further aggravated when to try to tilt the pelvis higher and hollow the lumbar, students create more push with their hands. The result is that the lumbar is still rounded and jammed, but now the thoracic spine is also flattened or hollow.

Quick Fix

Modify for tight hips and hamstrings, and prioritise keeping the spine in neutral by widening the gap between the feet, bending the knees and lifting the heels.

To allow for tight hips and or hamstrings, modify the foot and leg position.

Taking the feet wider apart gives more space at the hip joint for the hip flexion.

Rather than try to take the heels to the floor, prioritise getting as close as possible to the natural lumbar hollow. If you lift the heels and bend the knees, the tightness of the hamstrings has less ability to restrict the ability to tilt the pelvis in the desired way.

Even if you sense that the lower back is still round, don’t overcompensate by pushing further with the hands-rather, bring your weight forward into the hands so that the upper arms can roll outwards.

Long Term Fix

Reduce tightness and improve the forward bend by practicing simple non weight bearing mobility postures for the hips, hamstrings and lower back (such as Apanasana (Knees to Chest Pose) or Chakravakasana (Sunbird Pose variation; Hands and Knees to Extended Child Pose) and progress to more static stretches such as Sucirandrhasana (Eye of the Needle Pose) and Supta Padangustasana. (Reclining Hand to Big Toe Pose).

Getting there – Downward Dog from Whoa to Go

Try following these steps to get into Downward Dog with the spine in neutral and the shoulder blades wide apart. Don?t feel you have to go through all the stages-stay at stage iv). or v). if needed to prioritise keeping the spine undistorted.

Repeat moving between pics 1a & 1b 5 or 6 times.

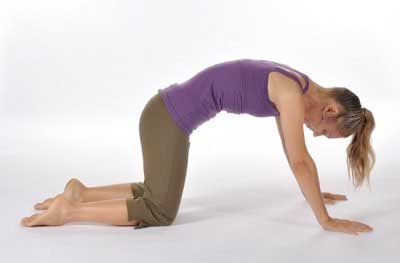

1a. Warm up: Chakravakasana – Inhale in this position

1b. Warm up: Chakravakasana – Exhale in this position

2. Come onto the hands and knees. Lift the chest away from the floor to separate shoulder blades at the back of the chest.

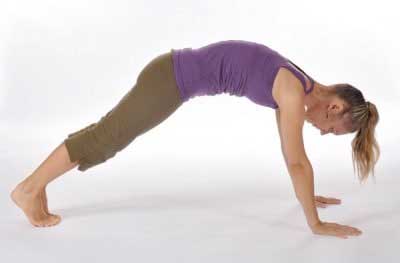

3. Lift the knees of the floor. Keep the shoulders above the wrists, and try to maintain the feeling of the shoulder blades spreading at the back of the chest.

4. Slowly lift hips up and back, keeping shoulder blades wide apart. Bend the knees and lift the heels tilting the tailbone to point towards the ceiling.

5. Keeping the heels high, lift the sitting bones even higher so that the knees become straight

6. If you can do so without rounding the lumbar, now lower the heels.