What limits you in a forward bend-and how can you best proceed? Tips from yoga master Flo Fenton.

This article first appeared in Australian Yoga LIFE magazine in 2011, issue 32, and is reproduced here with kind permission of AYL.

Benefits of Forwards Bends

Forward bends ask the spine to move into the primary curve, the shape that it assumes within the womb. Just as the backbends are stimulating and exhilarating, forward bends are soothing and calming. The backbends open the front of the body (the part with which we interact with the world) to its full extent whilst the forward bends fold the front of the body in upon itself. On an energetic and emotional level, forward bends ask us to be content with slowing down and looking within. More than any other group of postures, forward bends require surrender and patience (funnily enough, the attitude of a forward bend is a little like bowing, the attitude of humility) teaching us the true meaning of yoga. Flexibility can not be achieved by force….only with patient persistence. In this way forward bends teach us that not everything can be achieved by determination; we must learn to do our best, with an attitude of love, and then let go of attachment to the results.

Bio Mechanics of Forward Bends

The physical aim of a forward bend is to stretch out any tightness in the tissues along the entire back surface of the body, from the connective tissue on the soles of the feet, to the muscles along the backs of the calves and thighs, to the back of the hips, right the way along the muscles and connective tissue at back of the torso, alongside the spine and across the back of the shoulders, as even (gently) the ligaments between the spinal vertebrae themselves.

The desired type of forward bend in yoga asanas could be described as the action of bringing the belly and the thighs closer together. What we DO want is to tilt the whole torso forward in one line at the junction of the hip joints. What we DON’T want is to fold the front of the torso between the abdomen and the rib-cage, thus rounding the back of the spine and compressing the abdomen. Doing the former evenly stretches the back of the body and allows the front of the spine, chest and abdomen plenty of space, facilitating good oxygenation of the blood, optimal stretch of the intra-spinal ligaments, and reducing any compression on the intervertebral discs. The latter reduces the space in the abdomen and chest, compressing the abdominal organs and restricting breathing, and most importantly creates pressure on the front portion of the intervertebral discs where the spine is bending, and over-stretches the structures of the back. Practicing forward bends in this way is a good way to increase a stress and tension in the short term, and in the long term to pull muscles and create the conditions for torn ligaments and herniated discs. Furthermore, by practicing in this way, you won’t be increasing the requisite flexibility to eventually achieve the desired style of forward bend.

There are three types of forward bends, and each has its own benefits, and challenges.

Standing Forward Bends

Examples: Utthanasana/Standing forward bend, Padottanasana/Standing wide legged forward bend, Parsvottanasana/Side stretch pose

Standing forward bends all move with gravity- in fact gravity accelerates the movement of the torso towards the thighs so much that the muscles along the back of the torso, legs and outer hips must contract to control the descent, and maintain the stability of the hip joints and of the feet on the floor. Because of this need to maintain stability in the standing forward bends, some of these muscles never fully ‘let-go’.

Seated Forward Bends

Examples; Paschimottanasana/Seated forward bend Janu Sirsasana/Head to knee pose

Seated forward bends move with gravity also, but gravity has a far lesser effect here than in standing forward bends. In seated forward bends, whilst gravity is in our favour, the fixed position of the pelvis and the particular rotation of the femurs in the hip sockets may limit our ability to tilt the pelvis forward to its optimal angle, limiting the degree to which we can bring the belly to the thighs. (More on this later…see ‘What Limits Us?-Position of the Legs in the Forward Bend’)

Supine Forward Bends

Examples; Supta Padangustasana/Supine hamstring stretch, Urdvha Prasarita Padasana/ Upward extended feet pose.

Though often not classified as forward bends, these supine postures satisfy the requirement of bringing the belly and the thighs closer together. However, in these postures, with the torso lying on the floor, it is the legs which must come towards the thighs, thus these postures move against gravity. Because the back of the torso and hips are supported by the floor and are in neutral, the movement of the leg/s towards the torso is one of pure flexion at the hip joint/s; these are therefore the most effective postures to check, and to increase, the degree of pure flexion at the hips. Though supine forward bends don’t stretch the tissues through the back of the torso, they do provide the best and purest stretch for the backs of the legs.

What do we need in order for a forward bend to happen?

All three types of forward bend require the spine to initially be in neutral whilst the femurs or the pelvis move-either the femurs (legs) move whilst the pelvis stays still to bring the thighs closer to the belly, or the pelvis tilts whilst the femurs stay still to bring the torso closer to the thighs. Whilst both standing and seated forward bends require some spinal flexion (bending forward at the joints of the lumbar spine) at the end range of movement, in all three groups the primary and maximal movement is at the hip joints.

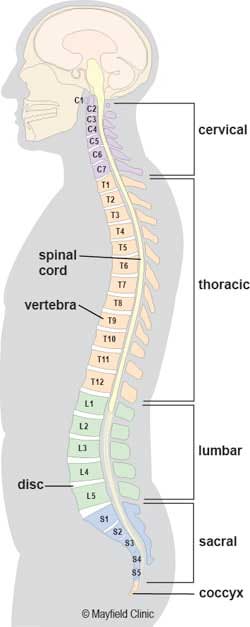

There are three key joints involved in forward bends:

- The hip joints; where the femurs (the leg bones) fit into the sockets of the pelvis (the hip girdle.)

- The junction of the pelvis and the spine S1-L5

- The joints of the lower spine; L5-T12

Diagram 1: Spinal vertebrae

Diagram 2: Pelvis and hip joints in Uttanasana

In a moderately flexible person, the degree of forward flexion (forward bend) from upright between the torso and the thighs is a total of 150 degrees. This amount of forwards bend is made up of:

- The ability to tilt the pelvis forward. A good ‘yogic’ forward bend begins with the forward tilt of the pelvis, and in our moderately flexible person, this forward tilt of the pelvis accounts for a massive 90 degrees of that 150 degree forward bend.

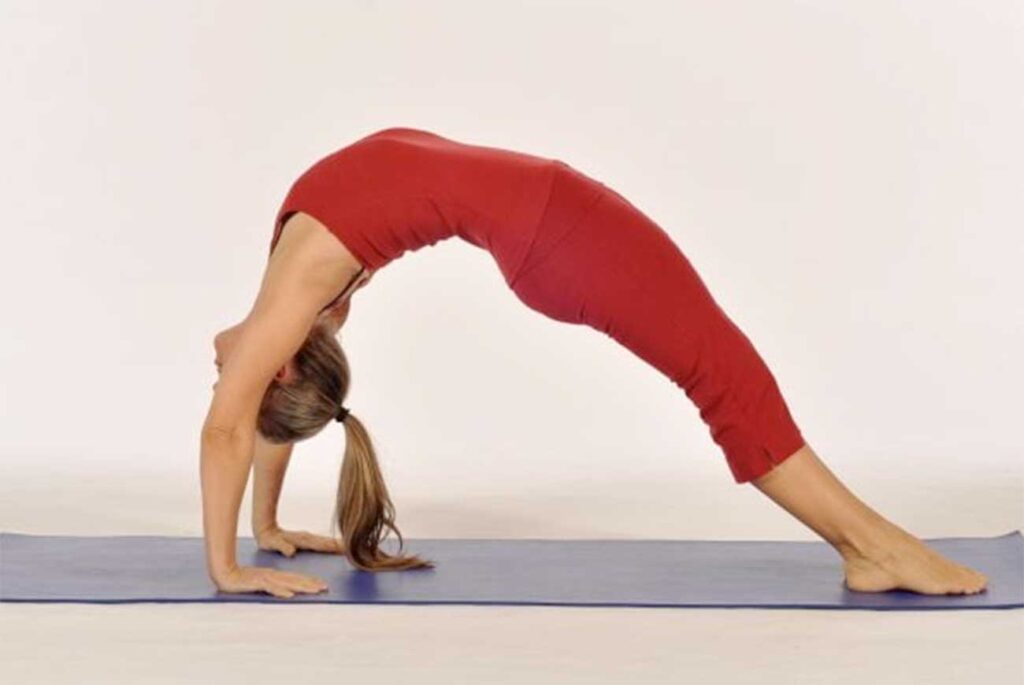

These two pictures show the rotation of the hips from their neutral position in standing to 90 degrees of forward flexion:

1. Standing Tadasana

2. 90 degrees forward flexion at the hips

- The lumbar spine must also move into a further total 60 degrees of flexion to complete the 150 degree forward bend. This is made up of:

- 18 degrees at the junction of the pelvis and the spine-S1-L5

- The remaining 42 degrees between the five joints L5 -T12. Progressively less movement is possible as we go further up the lumbar spine.

3. Once the pelvis has completed its 90 degrees forward flexion, the remainder of the forward bend must take place in the lumbar.

What Limits Us?

As we can see, by far the most forward bending action should happen when tilting the pelvis forwards at the hip joints …if it doesn’t the forward bend will be severely compromised. However in many students, there is little more than 30 degrees flexion possible at the hip joints.

So what limits the forward rotation of the hips in such students?

Skeletal Structure

At a skeletal level, the degree to which the pelvis can tilt forwards either facilitated or limited by the actual shape and size of the ‘ball’ and the ‘socket’ of the hip joints. In some people, there is a relatively wide and shallow dish shape that makes the socket, and a relatively small ‘ball’ or femur head, making rotation easy. Conversely, some have a deep dish shape with a narrower entrance for their socket, and/or a larger femur head which must rotate within it, creating a tight fit with minimal rotational ability. Males generally fit the latter pattern and females the former. However, these skeletal limitations can be to a great degree compensated for by increasing the mobility of the joints at a soft tissue level.

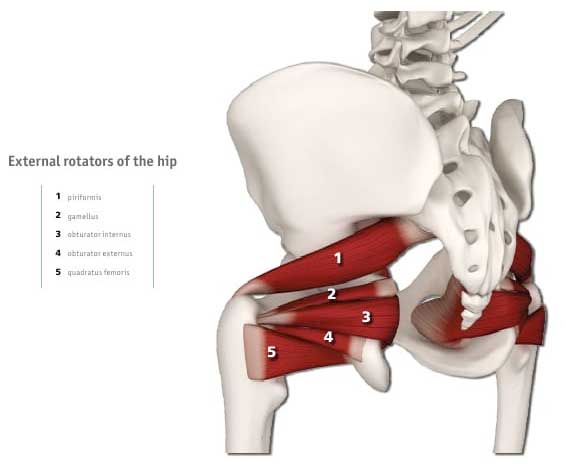

Tight Hip External Rotators

Tightness in the muscles that join the femur to the pelvis will greatly restrict the rotational movement. The external rotator muscles of the hips all connect the head of the femur to various points on the pelvis, and are arranged like fans. One of them, the piriformis muscle, connects to the sacrum, which is of course connected to and articulates with the spine.

If these muscles are tight, two major things will happen to limit the forward bend;

- The thigh bones will want to rotate outwards. In a pose such as Paschimottanasana, having the thighs (and the feet) rolled outward, makes it more difficult for the pelvis to tilt forward over the head of the femurs. (Try sitting in Dandasana and turning your thighs right out so that your feet turn outwards and then try to bend forward into Paschimottansana.)

- Tight external rotators shorten the gap between the head of the femur and the pelvis to such a degree that they cause the pelvis to tilt backwards (tail tucked under position). This means that the lower back also rounds. Any attempt to bend further forward from this position means that all the movement has to happen at the junction between the pelvis and the spine, and in the lower lumbar vertebrae, placing undue strain upon these joints and their ligaments and discs. (Try sitting in Dandasana and tilting your pelvis back so that you are sitting on the back of the buttocks, and then try to bend forwards.)

Tight Hamstrings

The hamstring muscles join the outside of the knee to the ‘sit-bones’ of the pelvis. They have to lengthen in all forward bends where one or both legs are straight. If they are tight, they too will limit the forward rotation of the pelvis and even tilt it backward.

Safe Practice Principles.

- Don’t Pull

The first and most important safe practice principal in any type of forward bend, whether you are experienced or a beginner, tight or flexible, is DON’T PULL! Using the hands to pull yourself into a deeper forward bend can’t and won’t increase the forward bend at the hip joints…all it can do is increase the forward bending at the junction of the pelvis and the spine and at the joints of the lower spine. Pulling is a good way to overstretch the sacroiliac ligaments in those who are flexible, and a great way to damage discs and tear muscles in those who are stiff.

- Spine and Pelvis in Neutral

The starting position for a forward bend should have the spine and pelvis in neutral. That means in standing that there should be a natural inward arch in the lumbar spine, with the back of the pelvis gently sloping backwards. In sitting, it means that the weight will be on the perineum, not the back of the buttocks.

- Begin at the Hips

If you are tight in the hips or hamstrings, before coming into the forward bend try to soften and allow your spine to find its natural curves. Soften the knees, so that they are a little bent; this will ‘unlock’ the hamstrings and allow the hips to tilt more easily. (In seated forward bends, use enough blankets cushions or bolsters-as many as it takes!- beneath the sitting bones to sufficiently tilt the pelvis forward and allow the lower back to arch. If the lower back still feels tense and rounded, bend the knees enough to relax the lower back.) Then begin the forward bend at the hips; think of lifting the tailbone up and back, and the pubic bone down and forward so that the whole pelvis tilts to create the forward bend. At the point where you feel the lower back rounding or any strain in the hamstrings, bend the knees more. Remember, the measure of the forward bend is how close the belly is to the thighs…not the chest to the shins!

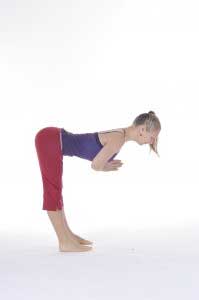

Standing forward bend incorrect. This is how you will end up if you have a lack of hip flexion in your forward bend, and keep the knees straight.

5. Standing forward bend – incorrect

If your belly is a long way from your thighs as in pic 5, it would be better to bend the knees as shown below.

6. Forward bend with bent knees – correct

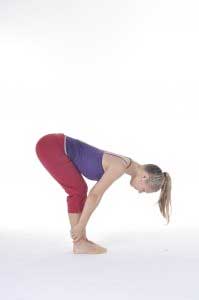

This is how you will end up if you have a lack of hip flexion in your forward bend, and keep the knees straight.

7. Seated forward bened – incorrect

If your belly is a long way from your thighs as in pic 7, it would be better to sit on 2-3 blankets and bend the knees as show:

8. Seated forward bend – correct

If you are very flexible in the hips on the other hand, or have any instability at the sacroiliac joint and/or have a very deep lumbar curve, increasing the forward tilt of the hips may aggravate these imbalances. For such students, it is better to lift the pubic bone slightly before coming into the forward bend, and focus on stretching the muscles of the lower back.

- Use the Breath

Before beginning the forward bend, connect to the breath. Encourage a smooth, even breath within your comfortable breath length.

Inhale as you lengthen the front of the lumbar spine. As you exhale, create the forward bend, and draw the lower belly inwards. Continue this breath and these actions with the breath throughout the forward bend.

Using the breath in this way does two things;

i). By maintaining our connection to the breath, we have a gauge…if the breath is smooth and easy, we are working with integrity and harmony. If the breath becomes disturbed, we have lost our integrity and need to back off.

ii). Maintaining the length of the front of the lumbar spine on the in breath and drawing the lower abdomen in on the out breath protects the lower back and sacroiliac joint from over stretching,

- Work the Adductors

In order to counteract the effect of tight external rotators which want to make the thighs roll outwards, work the inner thighs. In Paschimottanasana, this means keeping the thighs together, inside edges of the big toes touching. In janu Sirsasana, it means keeping the foot of the straight leg active, and not letting it roll outwards. In a symmetrical standing forward bend such as Utthanasana, it means working the feet on the mat as if you are pulling them in together, or practicing with a foam block between the thighs, and squeezing it.

Supplementary Practices and Ongoing Work

Stretch the external hip rotators in postures such as Eka Pada Raja Kapotasana (Pigeon Pose) or Supine Janu Sirsasana (Keyhole Pose)

Lengthen the hamstrings in a pure hip flexion such as Supta Padangustasana (Reclining Hamstring stretch pose). Modify by bending the passive leg, foot on the floor if very tight.

References:

Asana Pranayama mudra Bandha-Swami Satyananda Saraswati, 2002 Yoga Publications Trust

Anatomy and Asana: Preventing Yoga Injuries-Susi Hately Aldous, 2006 Eastland Press

Anatomy of Hatha Yoga-H. David Coulter, 2001 body and Breath Inc.

The Key Muscles of Yoga-Ray Long MD, FRCSC, 2006 Bandha Yoga

Principles of Anatomy and Physiology Seventh Edition-Tortora and Grabowski, 1993 Harper Collins