A how to guide to yoga backbends, by yoga master Flo Fenton.

This article first appeared in Australian Yoga LIFE Magazine issue 32 and is reproduced here by kind permission of AYL.

Backbends are among the most energising and exhilarating of the yoga asana groups, and are the postures that create perhaps the most openness and freedom in the physical body and beyond.

Many of us have a slightly rounded upper back and ‘closed’ chest area often due to long sitting slouched over a desk. This poor posture restricts the front of the body and gives rise to shallow breathing, and is associated with reduced levels of energy and even negative thinking. Backbends stretch and expand the chest, inducing freer, deeper breathing, creating greater oxygenation of the blood, strengthening the heart muscles, and raising metabolism, as well as creating strength in all of the muscles of the back to improve posture. Just by bringing the thoracic spine into extension, and opening up the front of the body we can create a feeling of upliftment. In their role as natural ‘anti-depressants’, the backbends therefore promote higher energy levels, and chase away sadness and fatigue.

The Mechanics of a Backbend-overview

What does it take to achieve a backbend?

Our ability to move into a backbend depends on several factors. In varying degrees for each backbending posture, we will need a combination of;

- STRENGTH in the back and hip extensor muscles, and

- FLEXIBILITY in the hip flexors and external rotators, and in the joints of the spine itself

To stay in, and move deeper into the backbend we will also need;

- STRENGTH in the muscles that stabilise the backbend and

- FLEXIBILITY in the muscles along the front of the body that will need to stretch, ie. the chest, abdomen and the front of the thighs.

To be truly comfortable in the pose, maintaining an easy, steady breath and practicing with long term sustainability in mind also requires;

- A relatively SMOOTH CURVE that moves evenly through the whole spine, without any one part of the spine becoming a ‘hinge’ from which all of the extension takes place.

Let’s take a closer look at the requisite bio-mechanics of a backbend.

Major muscles of the back involved in backbends

Backbending postures can be broadly categorised into two groups;

- Prone Backbends-Those in which we are lifting the spine into a backbend against gravity, performed from a prone (face down) position, eg Bhujangasana (Cobra Pose) Salabhasana (Locust Pose) and Dhanurasana (Bow Pose) and

- Supine Backbends- Those in which gravity assists the backbend, performed from a supine (face up) position, eg Urdvha Dhanurasana (Upward Bow Pose), Setu Bandha Sarvangasana (Bridge Pose) and Ustrasana (Camel Pose).

Prone backbends require more strength in the back extensor muscles (as we are working against the pull of gravity). Because of this, the prone backbends are the best ones to practice in order to create maximum strength in the muscles of the back that will then assist and support all of the backbends.

Prone and supine backbends are both, by definition, created by the spine moving into extension (ie a backbend), and several muscles are responsible for this action.

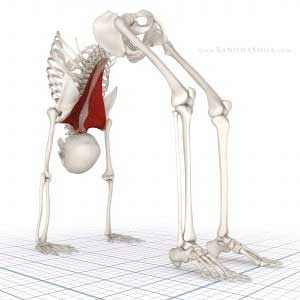

The Erector Spinae

The erector spinae muscles are the main muscles responsible for extending the spine. These are a group of three muscles pairs (iliocostalis, longissimus and spinalis) with one of each pair on each side of the spine. They all connect from the pelvis to the neck vertebrae, and each pair also has other connections. Together these are the muscles that when lightly contracted hold the spine upright during standing and sitting. When they contract further, their combined effort brings the spine into extension by shortening the distance between the pelvis and the neck along the back of the body. The iliocostalis also joins to each individual rib, thus pulling them closer together at the back when they contract. The longissimus also connects the transverse processes (bits that stick out to the sides) of the vertebrae, and the spinalis connects to the spinous processes (bony bits that stick out at the back) of the vertebrae. When these muscles contract they pull all the spinal vertebrae closer together along the back surface of the spine.

Erector Spinae in Urdvha Dhanurasana

The Trapezius

In Urdvha Dhanurasana Upward Bow Pose) the upper fibres of the trapezius contract to assist in lifting the upper body, by spreading the shoulder blades apart and turning them out, broadening the upper back to enable a firmer fit of the arm bones into their sockets.

In many deeper backbends, (such as Dhanurasana, Bow Pose, and Ustrasana, Camel Pose) the contraction of the lower trapezius muscles draws the shoulder blades down and in towards the spine, narrowing the back of the chest. This movement indirectly supports the extension of the spine.

Trapezius in Urdvha Dhanurasana

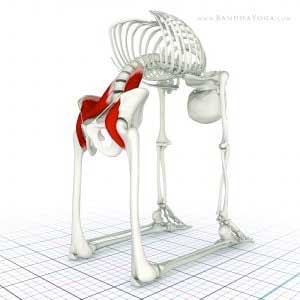

Hip Extensors

For many backbends to occur, there must also be extension at the hip joint; that is, the legs must move backwards relative to the front of the body. In order for this to happen, there must be adequate ‘give’ in the major hip flexors (notably the psoas that connect the lumbar spine to the inner pelvis, and that if tight we feel ‘pulling’ in lunge type movements) and adequate strength in the hip extensors (gluteus maximus and the hamstrings) to enable the pulling back of the legs. When the big muscles of gluteus maximus and the hamstrings contract, the whole back surface of the legs is shortened and the hip joints are pulled into extension, so that the legs follow the line of the spine and complete the curve, as in Urdvha Dhanurasana (supine example) and Dhanurasana (prone example).

Psoas in Ustrasana

Common Pitfalls-Where we get into trouble

Relative Movement at the Joints of the Spine-Hinging in the lower back and neck

In order for a backbend to occur, there needs to be movement between the vertebrae themselves to create the curve of the whole spine. Unfortunately however, all vertebral joints are not equal in their ability to move in the required manner. In fact, in most people, perhaps 75%-80% of the total extension of the spine occurs between only about 5 of the joints…about three in the lumbar and two in the cervical sections of the spine. Very little extension occurs by comparison in the thoracic section. There are three main reasons for this;

- The angle and length of the spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae limit their ability to move into extension (in other words, the bits that stick out at the back of these vertebrae just jam into each other after fairly minimal extension as compared to the lumbar and cervical vertebrae.)

- The thoracic section of the spine is surrounded by the rib cage, which limits its ability to move into extension

- Many people work at a desk and have some degree of rounding of the thoracic spine as a result. The muscles of the chest become tight and the muscles of the back become weak, further diminishing the ability to move the thoracic spine into extension.

This combination of anatomical and behavioural factors means that most of us use the neck and lower back as the only two places in the spine that really move much at all in day to day activities. These areas then become like ‘hinges’ moving back and forth whenever movement is required, whilst the rest of the spine remains fairly immobile. Then we go to yoga class, with the idea of increasing movement in locked up areas of the body, and strengthening parts that are weak. However, unless we are mindful, we simply enhance our habit patterns, using the most flexible parts of the spine to create nearly all of the extension required in a backbend, whilst the thoracic spine is hardly being asked to extend at all. This creates potentially increased wear and tear in those already overused joints in the long term, and in the short term creates an uncomfortable sensation of ‘jamming’ in the lower back or neck.

Remedy

To prevent jamming in the lower back or the neck, first create an intention or visualisation to create a smooth curve throughout the whole spine, in which each spinal joint plays an equal part in the total extension, and no one part of the spine has to bend more than another. Just by having this understanding and awareness, you will move with greater care and integrity.

The next step is to limit extension in the already over-used parts of the spine (lower back and neck). Then to try to create more movement in the parts that don’t move as easily (thoracic spine and chest area).

Think of initiating the extension at the thoracic spine, and only allowing the lower back and neck to extend to the point that they ‘match’ the extension achieved there.

Example: Slow Bhujangasana (Cobra Pose)

Lie on the abdomen, and place the palms on the floor beneath the shoulders. As you inhale, try to slowly ‘peel’ the front surface of the body away from the floor, starting at the sternum, up to about the height of the navel and no more. As you exhale slowly lower back down. Try to use the muscles of the back, not the hands, to create the movement. As you come up, keep the neck in line with the rest of the spine…don’t throw the head back. Only come up to a point where you feel that the lumbar spine is having to bend no more than the thoracic spine.

Practice five rounds.

C0bra – C0rrect

Cobra – Incorrect

Stabilising the Pelvis

We have already seen how, to prevent jamming in the lower back, there needs to be extension in the thoracic spine. Another piece of the puzzle to a functional, sustainable backbend with a smooth curve is stabilising the pelvis.

As we have seen, for many of the backbends to occur, there needs to be extension at the hip joints…in other words the femur bones (thigh bones) need to move into extension (backward relative to the front of the body) at the hip joints. For the femurs to move in this way, the pelvis needs to be stable. From an anchored pelvis, the gluteus maximus and hamstrings contract, lifting the femurs into extension. However, if the external rotator muscles of the hips are relatively tight, this pure movement of hip extension does not occur. Instead, the femurs follow the path of least resistance, and roll outward. You will see this in many yoga practitioners when they push up into Urdvha Dhanurasana (Upward Bow Pose)…their heels get closer together and their toes turn out. It can also be seen in Setu Bandha Sarvangasana (Bridge Pose) where the toes and inner feet ‘peel’ off the floor as the hips rise.

This turned out feet position is one in which the pelvis is then unstable; it is very likely that the force of trying to extend the hips in this position will cause maximum extension at the most flexible parts of the lumbar spine, again creating jamming in the lower back, and reducing the extension being asked of the thoracic spine.

Remedy

What can we do about this? Apart from stretching the external hip rotators as ongoing, supplementary work, we need to off-set the tendency of the thighs and feet to roll out or peel off the floor by engaging the stabilising muscles; these are the hip adductors (muscles of the inner thighs, whose job it is to move the thighs inwards towards the centre line), and ‘pada bandha’, or the foot lock, which when switched on anchors the feet to the floor to counteract the inward spiralling action of the adductors, and the outward spiralling action of the external hip rotators.

Example: Bridge Pose Vinyasa into Upward Bow Pose with a block

Start lying on your back with knees bent, and feet less than hip width apart. Make sure that the heels are not too far forwards of the buttocks, and that the toes are not turned out. Place a foam block width ways in between the thighs about midway between your knees and hips. Squeeze the block by working the thighs inwards. This is the starting position.

Inhale as you raise the arms over the head and slowly lift the hips to knee height. Exhale as you roll back down the spine, one vertebra at a time, taking the arms down. As you move up and down, try to maintain even pressure on the block, squeezing the thighs together. Anchor the feet by pressing evenly into the big-toe side ball of the foot, little toe side ball of the foot, and centre of the heel (pada bandha).

Practice 5 rounds.

Bridge Pose with block

For intermediate to advanced students:

Come back into the starting position. Place two foam blocks together between the thighs, so that the feet are a little wider than hip width apart. Have the little toe sides of the feet parallel. Place the hands under the shoulders. Inhale and as you exhale push up into Urdvha Dhanurasana (Upward Bow Pose) Keep even pressure with the thighs into the block, and anchoring the feet with pada bandha. At other times, when practicing without the block, take the feet wide enough apart so that they don’t have to turn out when you come into Urdvha Dhanurasana.

Upward Bow Pose with blocks

Supplementary Practices and Ongoing Work

- To help create more ‘opening’ of the thoracic area over the long term, passive upper backbends over a bolster or blankets can be used. Make sure that the extension in the lower back and neck is limited…support the back of the head with blankets, and bend the knees if necessary to keep the back of the pelvis flat on the floor.

- Continue to work towards strengthening the muscles of the back that support the total extension of the spine in prone backbends, always limiting the movement of the over-used parts of the spine

- Work to strengthen the stabilising muscles that support the backbend

- If needed work on flexibility of the quadriceps, psoas, external hip rotators, abdominals and chest area by targeted stretching (ie not just in the attempt at backbends)

- Take the feet wide enough apart so that they don’t have to turn out when you come into Urdvha Dhanurasana (Upward Bow Pose).

References:

Anatomy and Asana: Preventing Yoga Injuries-Susi Hately Aldous, 2006 Eastland Press

Anatomy of Hatha Yoga-H. David Coulter, 2001 body and Breath Inc.

The Key Muscles of Yoga-Ray Long MD, FRCSC, 2006 Bandha Yoga

Principles of Anatomy and Physiology Seventh Edition-Tortora and Grabowski, 1993 Harper Collins