Do you experience pain in the lower back/back of the pelvis-and is it aggravated by doing yoga? Read on to understand more about this commonly strained joint, what to avoid, and how to work to re-align it with careful yoga practice.

Identifying SIJ Strain

How do you know if that pain you are getting in the area of the lower back/back of the pelvis is sacroiliac joint (SIJ) strain?

Sacroiliac pain presents as pain that exists in a small spot, at the location of the sacroiliac joint. It is commonly felt more, or only, on one side. It can manifest as pain that appears during the transition between sitting in a chair and standing, or whilst coming into or out of certain poses, typically Trikonasana (Triangle pose), Parsvakonasana (Side angle pose), Janu Sirsasana (Head to knee pose), some of the twists, and coming out of some of the deeper lumbar backbends, (even though you might be quite comfortable whilst in the pose).

Pain and its location are not an accurate indicator of the condition; pain can manifest on the injured or un-injured side. If you suspect that you or your student has it, it is important to get the condition properly diagnosed by a health care professional such as a physiotherapist or osteopath.

Structure of the Pelvis/SIJ

What is and where is the SIJ?

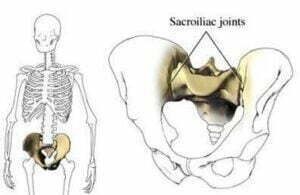

The pelvis is made up of:

- Two pelvic bones, (or hip-bones) creating the two halves of the pelvic bowl, and

- The sacrum

- The ‘V’ shaped sacral bone is a continuation of the spine that slots in between the two pelvic bones at the back

- The SI joint is literally the join between the two; it runs along the margins of the meeting surfaces of the sacrum with the ilia of the two pelvic bones

- The sacrum can move independently of the two pelvic bones at the SI joint in those who are flexible.

Function

How is it supposed to work?

The structure is set up mainly for child-birth! During childbirth the movement of the sacrum forwards or backwards within the pelvic bowl changes its shape. During the middle stages of labour, the top of the sacrum tips back in relation to the pelvic bones, which effectively opens the top of the pelvic bowl allowing the baby’s head to more easily enter. This movement of the sacrum is called ‘counter-nutation’. It is the same movement that yoga practitioners unconsciously create when performing a ‘whole body’ backbend in which the ischia (sitting bones) are held close together. (Think of ‘dropping back’ into Urdvha Dhanurasana/Full backbend from Tadasana/Mountain Pose).

During the final stages of labour the top of the sacrum tips forwards in relation to the pelvic girdle, effectively narrowing the top, but broadening the base (spreading the sitting bones apart). This creates space for the baby’s head to enter the birth canal. This movement of the sacrum is called ‘nutation’. It is the same movement that yoga practitioners unconsciously create in a forwards bend from the hips, in which there is a ‘spreading of the sitting bones’. (Think of coming forward deeply in Padottanansa/Wide legged standing forward bend.) Nutation and counter-nutation are passive movements of S1-either forwards or backwards, and are a natural, healthy part of forwards and backwards bending in the lumbar spine. These movements are essential to what we call the lumbo-sacral rhythm (see p. 84 ‘Yoga Body’-Judith Lasater).

This independent movement of the sacrum between the pelvic bones requires some flexibility at the SIJ. In the majority of the adult population, the pelvic bones and the sacrum are bound tightly, even fused, together. (Coulter, H.David, “Anatomy of Hatha Yoga” 2001, pp.142-144.) There is no movement at their S.I joints. However, yoga increases mobility at these joints, especially amongst women.

Pros and Cons of SIJ Flexibility

Those who have a high degree of sacroiliac flexibility can execute the deepest of all, belly to thighs forwards bends and almost-bent-double the other way backbends. (Coulter, H. David, “Anatomy of Hatha Yoga” 2001, p.328-332). The down side is that whilst the sacrum is in a state of nutation, and therefore ‘mis-matched’ from its usual place between the pelvic bones, strain is being placed on the S.I joints. Any further strain that is placed on the joints, due to force of pulling oneself deeper into the posture using the strength of the arms, for example, risks injury and displacement of the joint.

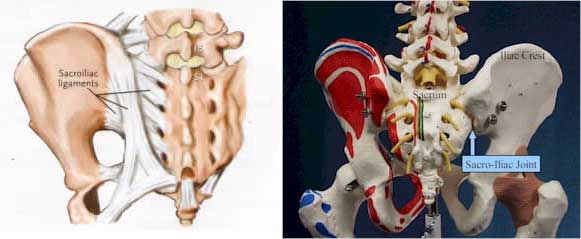

SIJ Stability

- The sacroiliac joint is at its most stable when standing upright, with equal weight on the two feet

- The weight of the entire torso pushing down on the sacrum (which is, remember, a continuation of the spine) locks it into place between the two halves of the pelvis

- The natural lordosis (inward arch/hollow) in the lower back which occurs in this position is also part of promoting maximum stability in the sacroiliac joints

- In this position, the edges of the sacrum line up perfectly with the meeting surfaces of the pelvic bones, and there is no strain on the sacroiliac joints

- This is why those with weak or damaged sacroiliac joints often find it more comfortable to stand

Why Does Sacroiliac Pain occur mainly in Women?

One reason is hormonal. The menstrual cycle, pregnancy, childbirth, and lactation all have an associated change in hormone levels which affect the SIJ and make it more flexible. The sacroiliac joints are designed to let the bones of the pelvic bowl ‘come apart’ slightly, (due to the sacrum to moving forwards or back within the pevic bowl, changing its shape) during childbirth. (Coulter, H. David, “Anatomy of Hatha Yoga” 2001, p.330)

They are therefore affected by the hormones oestrogen, progesterone and relaxin. Every month in the week before menstruation, when oestrogen and progesterone levels are highest, the female sacroiliac joint is more flexible…and more vulnerable. (This is why those women who suffer from sacroiliac pain may find it is worst at this time.)

Another reason is anatomical.

The greater width of the female pelvis tends to increase the degree of torsion at these joints during side to side movements of the hip bones, as in walking.

Causes of SIJ Strain

- Scoliosis, which leads to uneven pressure on the SI joints and eventual strain ·

- Habitually flattening out the natural lumbar curve in standing postures destabilises the joint ·

- Trying to keep the hips perfectly square in asymmetrical open hips standing postures such as Trikonasana (Triangle Pose) Virabhadrasana II, (Warrior 2 Pose) and Parsvakonasana (Side Angle Pose) creates uneven torsion on the SI joints ·

- Trying to keep the pelvis static and then moving from the lumbar into standing or seated twists

- Adjustments in any of these postures which try to move the hips ·

- Overstretching/pulling/adjustments in seated forward bends ·

- Asymmetrical forward bends with a twist, e.g Janu Sirsasana practiced with bent knee side of pelvis tilted back which aslo produce uneven torsion

Flattening the lumbar arch

‘Tucking the tail under’ in standing postures may engage the abdominal muscles, but it de-stabilizes the SIJ. (Should we need to engage our abdomen in order to simply stand upright?) By tucking the tail under, we have moved the lumbar spine into flexion; the weight of gravity no longer moves down through the spine to cement the ‘keystone’ of the sacrum into the pelvis. If we lose the natural lumbar curve, we lose the healthy lumbar pelvic rhythm, and the whole spine becomes less stable.

Practicing finding the natural lumbar arch in Tadasana and then taking that through into asymmetrical standing postures such as Trikonasana and Parsvakonasana is often enough to take chronic SIJ pain away.

Tadasana Tail Tucked-May aggravate or cause SIJ strain.

Tadasana-with-natural-lumbar-arch.

Twists

- To maintain SIJ health, it is best to let the pelvis move with the spine into the twist.

- (In fact, the sacrum is a part of the spine!)

- In seated twists, sit the bent legged side hip further back.

- In standing twists (such as Parivrtta Trikonasana) let the hip on the front legged side roll back so that the whole pelvis moves into the twist.

Asymmetrical forward bends

- In asymmetrical forwards bends the sacrum may be in a state of nutation (‘mismatched’ from its normal mating surface with the pelvic bone) on one side only

- This makes the sacroiliac joint on that side especially vulnerable to strain

- For example, in Janu Sirsasana, it is much easier to bend forwards (and nutate the sacrum) on the straight legged side

- The bent knee side of the sacrum remains in place, joined to the pelvic bone on that side. The two halves of the pelvis are going in different directions, with the sacrum doing one thing at one of the joints, and something else at the other

- Even stiff practitioners who don’t have that much sacroiliac flexibility can injure a sacroiliac joint by leaving the pelvis behind and their tail tucked under, skewing the hips, bending at the waist, and then pulling, in Janu Sirsasana.

Remedy

- Rule number one is: Don’t pull! The key to a pain free S.I joint is not to stretch it too much

- Next, avoid placing the sitting bone on the bent knee-side further back than the other, thus setting up a twist in the hips before you even begin

- Try to align the front of the pelvis square on

- Think of moving forwards with the front of the belly long, and the weight of the body rolling onto the front of the sitting bones, so that the whole pelvis moves forwards in a continuous line with the spine

- These actions will minimise the degree to which the two halves of the pelvis are going in different directions.

Yoga Therapy for SIJ

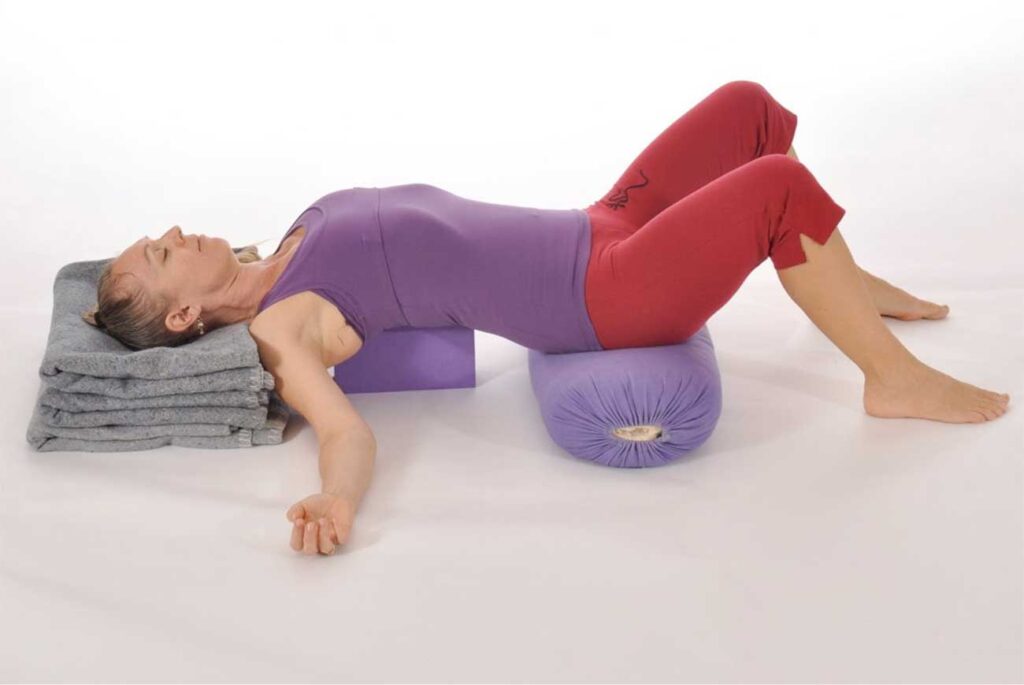

- Acute phase

- REST

- Re-align if possible

- Consider use of sacroiliac belt, available through physiotherapist websites, or improvise

- Sub-acute phase

- Mobility-gentle movement without weight bearing in forward bending, back bending and twisting position

- Regain natural lumbar arch in standing

- Chronic Phase

- Strength/stability-Strength/stability-strengthen with weight bearing movements-especially work on good abdominal and lower back strength-start supine and build.

- If you’d like to attend an online workshop on this topic free to Yoga Australia Members and receive 2 CPD points, please register for the Yoga Australia Nth NSW Teachers Meeting 27th Feb 2-4pm AEDT -bookings https://www.eventbrite.com.au/e/nsw-state-meeting-working-with-sacroiliac-joint-dysfunction-workshop-tickets-132921739501

References

- Coulter, H. David, 2001 “Anatomy of Hatha Yoga”

- Lasater, H. Judith, 2009 “Yoga Body”

- Pullig- Schatz, MD. Mary, 1992 “Back Care Basics”